XVI-XIX siècle

Les objets

Dessin

Head of a Man

In 1595, Cesari was entrusted with the decoration of the Palazzo dei Conservatori on the Campidoglio in Rome. The painter was to depict the great events in the history of the city. The first fresco focused on the she-wolf and Romulus and Remus. This drawing was a preparatory study for the character of Faustulus, the shepherd who took the twins from the bottom of the Palatine Hill and gave them to his wife to bring up. There is a striking contrast between the powerful modelling of the torso and the sensitive movement of the face, which expresses the uneasy relationship between body and soul found in the later works of Michelangelo.

Dessin

Portrait of the Miniaturist, Ercole Pedemonte

Ottavio Leoni was admired in his lifetime for his drawings of the great artists and men of science of his time. He was particularly known for his portrait of Caravaggio, dated 1621. This portrait of the miniaturist Ercole Pedemonte was painted in 1614, as indicated in the annotations signed by the artist at the bottom of the drawing. The model was most likely a close friend of the artist as his face is found again in the painting of Suzanne et les vieillards [Susanna and the Elders] conserved in Detroit.Leoni always used the same technique in his drawings: the facial characteristics of the characters are executed in pierre noire, the light areas are suggested using white chalk, and the paper he used was blue, grey-blue or buff.His portraits were produced “alla macchia”: after just one sitting with the model, Leoni depicted the model in a few moments, like a stain (“macchia”) spreading out over the paper. The speed of execution and absence of a model when painting the portrait underlines the artist’s originality. We do not know for whom his drawings were intended, but we do know that some, like the one in the Magnin collection, were later reproduced as engravings.

Dessin

Cavalry Charge

At the beginning of the 17th century, Courtois introduced a genre that promised to be a great success. His battle scenes were in demand all over Europe. Sketches like this one formed a repertoire of ideas that he turned to when creating more complex pictorial compositions. Here we find vibrancy in the line, barely sketched figures, a simple landscape suggesting distant horizons, with dynamic spirals forming the clouds. His unusual portrayal of the horses distinguishes them from the stiff, stereotypical depictions of his contemporaries. The wash highlights give substance to the figures in the foreground. The lighting – created here by leaving the paper blank – enhances the hindquarters, the silhouettes in the background and the extent of the battlefield.

Dessin

The Golden Calf

This rather un-Academic artist brings together two of his favourite subjects here: religious scenes and bacchanalia. To the scene of idolatry, Lafage adds a reference to a drinking spree in the foreground, while at the top of the page, Moses, tablets in hand, is in conversation with God.Lafage never showed any interest in rendering depth or distance. Skilled in pen and ink drawing, he took great care in depicting the body of model, a result of his detailed training in morphology. His representation of objects and elements of nature is more cursory, achieved through a rather special system of parallel lines. His style owes less to 17th century French art than to Annibale Carrache and Michelangelo (the venerable ancient figure on the right seems to have come out of an Italian Renaissance painting).

Dessin

St John the Baptist in the Desert

Towards the end of his life, Boucher moved away from the exuberance and preciousness of the Rococo period and turned to Rembrandt’s chiaroscuro and introspection for a means to dramatise his subjects. Here, St John the Baptist’s body is modelled by the light, in a scene that looks more like a vision than a prayer. The transition from dark shadows highlighted with pastel towards luminous whites, hints at the saint’s solitude and introspection. The artist takes the character’s pose and the powerful shafts of light penetrating the forest behind him, from a painting in Padua on the same subject, which was thought, in the 18th century, to be by Rubens. The introspective nature of this scene makes this drawing an unusual work in Boucher’s oeuvre.

Dessin

Jean-Baptiste GREUZE, "Étude de chien"

1764

Dessin

Hercules Slaying the Hydra

This Baroque drawing was possibly inspired by the painting of the same subject by Guido Reni (Musée du Louvre). It was dated by establishing a link with Le Triomphe de Claudius Metellus [The Triumph of Claudius Metellus] (Musée Atger), a drawing signed in the same way and dated 1770. The free technique of the wash emphasised by the tension in the pen and ink work helps the dynamism of a painting that is almost Romantic in its expression.

Dessin

Caricature of Lemonnier playing the Flute

Among the numerous caricatures of his fellow students that Vincent produced during his stay at the Académie de France in Rome, this red chalk drawing stands out with its unusual half-length framing and the spectacular freedom of definition. The model can be recognised as Anicet Charles-Gabriel Lemonnier (1743-1824), the history painter from Rouen who won the Grand Prix for painting in 1772, and whom Vincent had met at Vien’s studio.

Dessin

he Palace of the Estates of Burgundy and Statue of Louis the Great, in Dijon

When viewing the Palais des États de Bourgogne from the east, we see the wing built by Jules-Hardouin Mansart. The Grand Condé had called on Louis XIV’s leading architect to design the outer arcades in the form of a semicircle, and this work was finished in 1689. Aligned with the railings, the gate of the Logis du Roi (on the right in the drawing) disappeared during the construction of the east wing shortly after Lallemand finished his drawing. The equestrian statue of Louis XIV, designed by Étienne Le Hongre, was invented by Mansart to give definition to the royal square and to establish a visual counterpoint and dynastic link with the tower of Philippe le Bon (visible on the far right).

Dessin

Jean-Jacques de BOISSIEU, "En promenade"

1786

Dessin

Study for the figure of Plato in ‘The Death of Socrates’

This is one of the final studies for the character of Plato, at the foot of his master’s bed in the painting commissioned by the painter’s friend, Trudaine de la Sablière, in 1787 (now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New-York). The death of Socrates was a popular subject in the later decades of the Ancien Regime; Diderot recommended it to artists in his Traité de la poésie dramatique [Discourse on Dramatic Poetry] (1758).Père Adry, a Hellenist, had advised David to give Plato (who in fact was not present at this scene) an immobile pose. The face, hands and feet are barely sketched, whereas the classical clothing is depicted in great detail. He combines the softness of the falling folds – in keeping with the prostrated position of the figure – with a sculptural definition of the clothing expressed through the precision of the drawing and the dynamic of the shadows. In the opinion of the Neo-Classical theorist Winckelmann, drapery was a defined means of achieving the ideal style.

Dessin

Jean-Guillaume MOITTE, "Un Sacrifice"

1792

Dessin

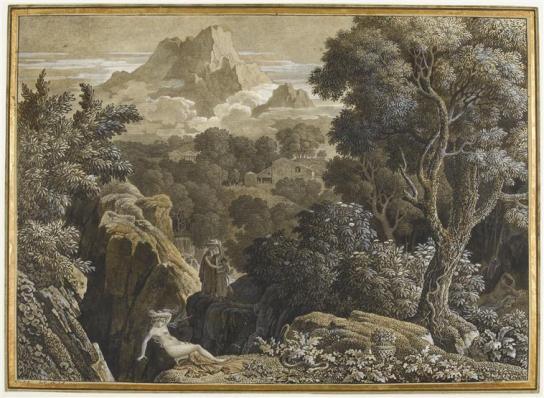

Landscape with a Snake

This luxuriant, imaginary landscape has an illustrious forbear in the work of Poussin. To the elegantly drawn vegetation in the foreground, the result of sharing a studio with the landscapist Péquignot, the artist has added the pyramidal form of the mountain, giving a monumentality to the composition. A cultivated man, Girodet has enriched this landscape with a literary aspect: the scene could be a reference to the story in Virgil’s Georgics of Eurydice falling into Hell. The artist plays on the contrast between the gracefulness of the figure lying down on the right, inspired by the famous Ariadne Sleeping and used for the Endymion painted in the same period, and the feeling of the Sublime heightened by the imminent fall of the female figure: two of the focal points in the Neo-Classical aesthetic.

Dessin

Portrait de Luigi Fantuzzi di Belluno

An album in the Musée Napoléon in Rome contains a series of portraits drawn from life, with a technique very similar to this one in the Musée Magnin. They are often accompanied – as is this one – by handwritten notes, one of which leads us to believe that it was executed during the Siege of Genoa in 1800. The subjects in the portraits, from various places in Italy, are probably patriots who had come to join the French troops during the Revolution. It is likely that the young beardless men with unkempt hair were Wicar’s fellow adventurers during the Napoleonic Wars. At the beginning of the 19th century, this artist from Lille began a brilliant career as a portraitist, revealed in dozens of drawings in charcoal or, as here, in pencil, characterised by incisive lines and regular hatching to enhance the face. The artist subtly evokes the model’s facial expression, personality and state of mind.

Dessin

Guillaume LETHIÈRE, "Les Deux frères"

vers 1807

Dessin

The Death of Atys

This sheet fits into the Neo-Classical movement that appeared at the end of the 18th century, influenced particularly by Jacques-Louis David. Dramatising the subject, Meynier puts all the vitality into the human figure, whether standing ready or collapsed with exhaustion after a heroic feat. The Exemplum virtutis here is expressed in the drawing, that is in the “style”, a crisp outline defining the forms. In the foreground, the body of the Phrygian god Atys, standing alone, has a counterpoint in the figure of the nymph he loves and who is dying. Dominating this desolate group, the expression of the jealous goddess Cybele focuses the drama. The emphatic language of the gestures (taken from the great Italian Renaissance models), the intense pen and ink work of the draperies and the expression of desolation on the faces do not permit any psychological insight; the heavy outline of the forms reflects moral determination. The only exception to the severe line and expression is the languid, naked body of the young Atys, borrowed from David’s Barra.

Dessin

Mazeppa Bound to the Hindquarters of a Wild Horse

We know that the legend of Mazeppa, popularised by Byron throughout Romantic Europe when his poem was published in 1819, fascinated Delacroix, and his Journal shows that he often thought about illustrating the adventure of this young Polish page who was bound naked to a wild horse as a punishment for committing adultery with the wife of a Palatinate Count. However, in the whole of his oeuvre, we can only find one small painting (Cairo) and one watercolour (Helsinki) on this subject. We can also link these, through the theme, to his drawing in the Louvre, Cheval renversant son cavalier [Horse unseating its Rider] (Roger-Marx Collection), as well as to two other drawings on this subject, also in the Musée du Louvre.The study in the Magnin collection probably illustrates a moment in the poem expressing the Romantic theme of man’s struggle between his innermost aspirations and the injustice of fate, and thus allows the artist to create one of the lively compositions that he so liked. It depicts the moment when Mazeppa is tied to the wild horse. The dense hatching in this beautiful graphite drawing brings the image into strong relief recalling some of the studies for La Mort de Sardanapale [The Death of Sardanopolius] and for Les Massacres de Scio [The Massacre at Chios], enabling the work to be dated to 1825-1830.

Dessin

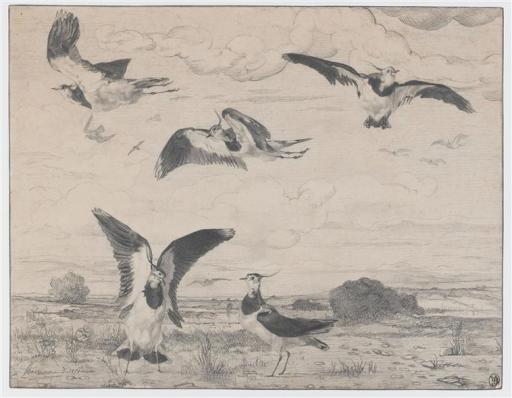

Félix BRACQUEMOND, "Les Vanneaux"

1851 ?

Dessin

Sir David WILKIE, "Le Jeudi Saint à Gênes"

1827